By Jackline A. Olanya

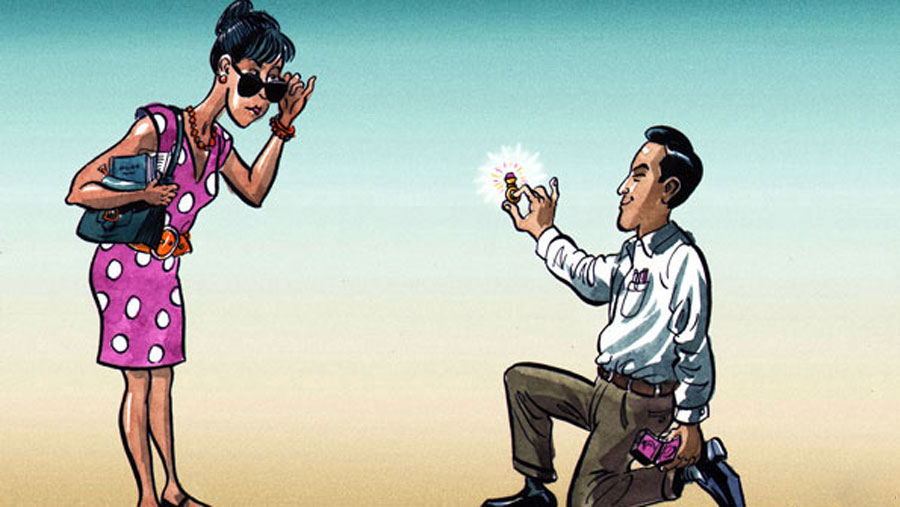

Arranged marriage. The very phrase seems like a contradiction in terms: “Marriage”—at least in the fairy tales and romantic comedies conjures up eternal, sin-free love, while “arranged” sounds horribly practical—like some overbearing outside force that reaches in from beyond and spoils the romance of it all. It certainly seems like something from a long ago outdated era. Surely, this archaic custom has nothing to do with you, the modern bride!

In fact, arranged marriages remains strikingly common around the world, in various forms and degrees: in southeast Asia; where couples are matched according to family status and class; among certain religious sects and among royal families; and yes — in Uganda,’ in rural villages as well as elite families who send their children abroad. Even in the modern Western world, the Internet is fast creating new forms of arranged relationships via mail order brides, lonely hearts chat rooms and other virtual matchmakers—all there to give fate a little push.

By definition, arranged marriages are unions that are engineered by someone other than the bride and groom, commonly curtailing or eliminating courtship altogether. They may have been more common long ago, but arranged marriages still take place all the time in modern Uganda and elsewhere in Africa.

We have cases where church members will find a mate for a person, or a concerned aunt helping out their overly growing nephew to find a mate. The practice, for example, is still quite common among the Vai people of western Liberia. James Klemii, a social worker on a yearlong exchange programme to Uganda, remarked that arranged marriages happen all the time back home in Liberia. Like many arranged marriages, they’re undertaken because the families involved want to consolidate and cement their economic power, class status and friendship. A Vai man may simply come to his young son one day and announce that a wife has been chosen for him. A date is set for the boy and his family to visit the prospective bride’s home for introduction (sound familiar?) It might well be their first meeting.

The young couple is given time within the ceremony to talk and get acquainted. Meanwhile, traditional rituals that hold deep meaning are performed. Kola nuts (bitter nuts containing caffeine that are chewed throughout West Africa) that have been put in bowls containing salt and pepper are eaten by members of both families to demonstrate that they are giving their hearts to one other and welcoming the new acquaintances as family members.

The groom’s family showers the lady’s family with gifts— much like our own Baganda custom—though they commonly offer palm oil, rice and a suitcase of clothes. If the lady in question is known to be a virgin, some money is included in the bride price. James added that the lady may be told by her father, “This is the man we have for you; we think he is a good man for you to marry.” Her father then turns to his ‘in-laws’ and says, “We agree that our daughter marries your son.” Sometimes the bride may be asked for her consent, and she may be hesitant to give her approval. If she’s “shy” or not ready to answer, the visitors are sent home and an “official” meeting for the two is organized in order for the pair to get to know each other better. Of course, after all those gifts it’s probably pretty hard for her to say no. Before you know it, a wedding usually follows.

Arranged according to culture

In Uganda, arranged marriages remain common but not quite as widely spread, as rumours that someone’s marriage may have been arranged are not taken very well. People tend to be quick to deny that their marriage was a setup; arranged marriages are—not surprisingly—regarded as neither hip nor fashionable among the young, who echo the Western idea they have a right to choose who they want to marry.

Of course, arranged marriages are more common among certain tribes, even today. The Bahima of Western Uganda, for example, traditionally aim to keep their wealth (cattle) within the family. It’s not uncommon to find a Muhima married to his or her cousin. (Another historically common byproduct of arranged marriage in many cultures.) But in Uganda, as elsewhere, arranged marriage has taken on a more subtle, muted form in many cases. (It’s much like polygamy: still practiced, but often in a less formal fashion than it once was.)

As always, it is closely related to class and perceived appearances. Extremely wealthy parents may seek out a bride or groom for their son or daughter of marriageable age from among the children of their colleagues and classmates. Wanting one’s daughter or son to marry into a posh family with a recognisable name is a sentiment as old as the hills. The wedding is a big event where they seek to impress and set precedents.

Among people living abroad

Among Ugandan expatriates—those living abroad—arranged marriages are also common, especially among men who are apparently willing to give up their country physically but not culturally. Their families back home in Uganda might agree that their sons (and daughters) are better off with “home girls” (and boys) who will be more likely to maintain some semblance of Ugandan culture even while residing in a foreign land. There are Ugandans living in the United States, Europe and Asia who have been there for years and failed to meet their mates —for whatever reason. Distressed relatives and friends launch a search on their behalf for possible Ugandan suitors who might be qualified and interested. Sometimes the parents of an eligible Ugandan lady here at home are approached on behalf of the family of the Ugandan bachelor abroad even before the lady herself is. Of course, she is then encouraged to accept the “proposal” in exchange for a better life in a developed country. Before long, emails are exchanged, and representatives are being sent from abroad to participate in an introduction ceremony.

A (usually posh) wedding is arranged, and the gentleman in question flies in from his glamorous Western home to marry. A few days later, he gets back on the plane with a new bride on his arm whose head is invariably filled with images of big, rich houses and cars, not cold winters and scouring the aisles of Western supermarkets for matooke. In countries all over the world, this version of arranged marriage between expatriates and spouses from back home plays out again and again—motivated by economic disparities and cultural norms.

So do arranged marriages work?

For his part, Klemii believes they do, grounded as they are in common backgrounds, goals and (presumably) beliefs. But a local banker we’ll call Anita Nambi cautions young women and men from hurriedly jumping into such arrangements just for the sake of matrimony.

Her brother, who we’ll call John, had gone to the UK to further his work and studies. Their father, who apparently believed John was ready to settle down, fixed him up with a receptionist that worked at a business partner’s office (who we’ll call Rebecca.) Upon recommendation from his colleague, he engaged her to his son, and the pair is now living as man and wife in the United Kingdom. But after barely a year of marriage, trouble in paradise has already been detected: John says Rebecca is overly demanding and expects things to work like they do back home.

This is not to say arranged marriages do not work. But one should get into one as cautiously and as well prepared as they can, because marriage is for a lifetime.